Technical Background

Technical Background on LLMs

In order to discuss how LLMs can affect life in our democracy and society itself, we first need to look at LLMs themselves.

What are LLMs?

The acronym LLM stands for Large Language Model. They are trained to understand and generate human-like text. Put simply, they predict which word is likely to come after another word, like the autocomplete on your phone when you write a text message. With this basic mechanism, LLMs can answer complex questions in various fields, write creative stories, or even compose poetry. They can imitate different text styles or authors and write programming code. Most state-of-the-art LLMs can do this in multiple languages and translate between them. Not all LLMs are equally good at these tasks, sometimes they are trained to be good at writing like Shakespeare and sometimes they are really good at chatting with the user. This distinction is made during training, so let’s look at how LLMs are trained.

How do LLMs work?

The basis of every LLM is a lot of data. The data used for LLMs are text fragments, like whole Wikipedia articles or anything else that is available on the Internet. Depending on what the developers want the LLM to do, they have to clean the data. This means that they have to remove parts of the text, such as swear words or instructions on how to build a bomb, since these are things that should not come up in a conversation with an LLM. However, the LLM doesn’t read and understand the text the way a human would. For an LLM, words are represented as word embeddings. The LLM doesn’t have an internal dictionary like a human might have, where it might say something like “cat noun [ C ] [/kæt/] a small animal with fur, four legs, a tail, and claws, usually kept as a pet or for catching mice” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2023). Instead, “cat” is represented as a multidimensional unique vector that captures not only its meaning, but also the role it plays in a sentence and the context in which it might be used with other words. This is a pretty clever way of representing words, since we don’t have to define each word and how it is used. It also allows you to perform simple algebraic operations on the words. For example, one could compute Paris - France + Italy to get the word vector for Rome (Mikolov et al., 2013). Of course this elegance comes with the drawback, that the vectors are too complex to be understood by humans, which makes the internal workings of LLMs difficult to interpret. Nevertheless we can look at the internal design of LLMs.

As you know, your phone often predicts complete nonsense. Simply predicting the next most likely word is not enough.

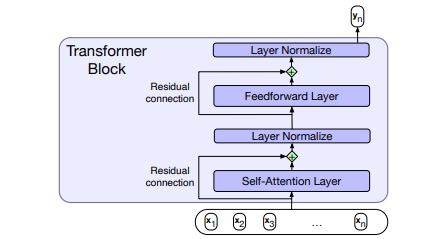

Therefore, the heart of most LLMs is a so-called transformer block, which looks like the first figure. The transformer consists of a self-attention layer. This means, that for each word in the sentence, an attention value is calculated for all the other words in the sentence. To do this, we compute a key, value and query matrix and concatenate them. We get a weight value, that expresses how important each word is for the context of the current word. In fact, the layer computes a multi-headed self-attention. This allows the attention algorithm to capture multiple aspects of importance in the input. This attention algorithm is why, unlike your phone, the language model can keep track of long-term dependencies and write long coherent paragraphs without being too redundant.

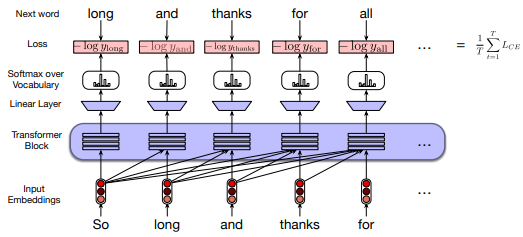

So how does the transformer block fit into the big scheme of things in the model? Let’s zoom out and look at the next graphic.

As you can see, we start with the word vectors as input. Then the transformer block calculates the attention for each preceding word and outputs a distribution showing how likely each word from the entire vocabulary is to follow our current input word. In the training, we know which word should actually follow, so we can simply calculate the error between the predicted word and the actual word, to give the model a feedback on its performance. The next word is then used as input to the model and we iteratively build a sentence.

Up to this point, most LLMs are roughly similar. They differ in vocabulary size, data size, and number of parameters, but the general operation is the same. This is where fine-tuning comes in. An LLM designed to answer scientific questions should be accurate and concise, while a chatbot LLM can and should answer more verbosely. Since it is used for entertainment, it is not as important that it can summarize complex scientific facts. To achieve this specialization of LLMs, Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF) is used. Since it is too complicated to define every goal an LLM should meet (be true, be concise, be friendly, be harmless, etc.), human developers simply rank several outputs of the model to the same prompt from best to worst. The model then implicitly learns which responses are desirable and which are not (Ouyang et al., 2022).

Still, there are some things that LLMs can’t do, and we need to be aware of this when using them. First, most LLMs only have training data up to a certain point. This is to prevent the model from learning a bias from the input data. Therefore, some models can’t answer questions about historical events after the time of their training data.

They can’t make moral judgments like humans can, because they don’t have a conscience. They can only reflect the moral viewpoints they have encountered in their training.

Finally, they are not one hundred percent correct. They rely on probability, and that doesn’t guarantee correct answers, so we have to question the answers of an LLM.

Let’s keep this in mind as we consider the following scenarios of how LLMs might influence our democracy.

Figures:

Jurafsky, D., & Martin, J. H. (2023). Speech and Language processing: An introduction to natural language processing, computational linguistics, and speech recognition. In Prentice Hall eBooks (3rd ed. draft). https://web.stanford.edu/~jurafsky/slp3/

References:

Cambridge Dictionary. (2023). Retrieved August 20, 2023, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/cat

Mikolov, T., Chen, K., Corrado, G. S., & Dean, J. M. (2013). Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv (Cornell University). http://export.arxiv.org/pdf/1301.3781

Ouyang, L., Wu, J., Xu, Almeida, D., Wainwright, C. L., Mishkin, P., Zhang, C., Agarwal, S., Slama, K., Ray, A., John, S., Hilton, J., Kelton, F., Miller, L., Simens, M., Askell, A., Welinder, P., Christiano, P., Leike, J., & Lowe, R. J. (2022). Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. arXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2203.02155

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, L., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. arXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1706.03762